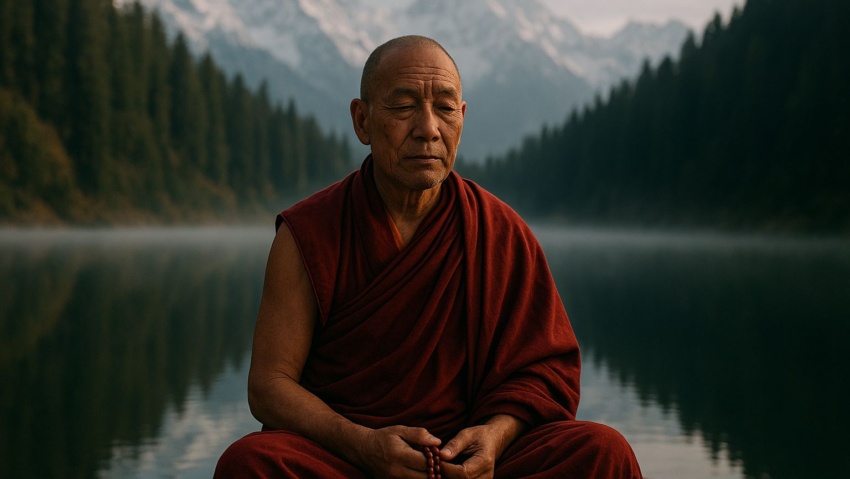

Tenzin’s eyes hold the kind of peace that comes from decades of sitting with difficult questions without needing immediate answers.

Tenzin’s eyes hold the kind of peace that comes from decades of sitting with difficult questions without needing immediate answers.

Sister Mary’s hands tell the story of 78 years spent coaxing rubber tree roots across mountain streams, training living architecture that grows stronger with each passing decade.

Pemba’s weathered face tells the story of 45 years lived at altitudes where most people struggle to breathe, guiding travelers through landscapes that shift between breathtaking beauty and life-threatening danger.

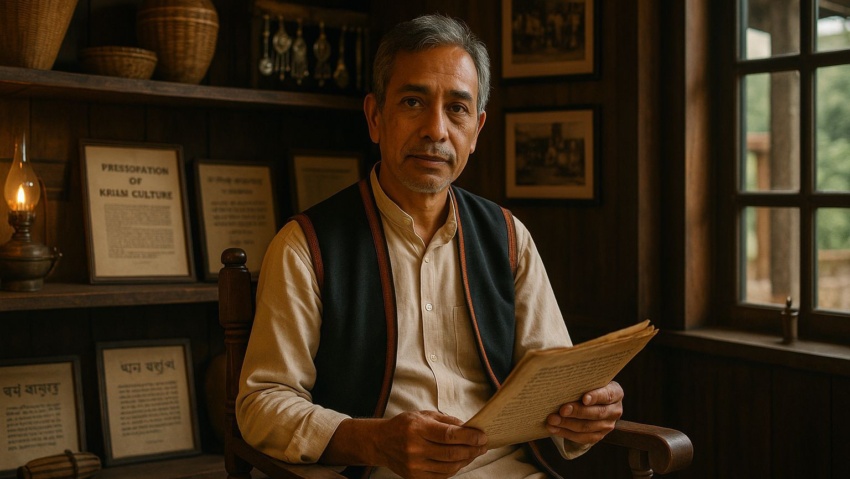

Pastor William’s study walls are covered with photographs of disappearing Khasi traditions, each image a small rebellion against the amnesia that threatens indigenous knowledge.

Pandit Ramesh’s hands move with the precision of someone who has prepared thousands of prayer offerings for the most dangerous pilgrimage in India.

Lobsang’s hands turn the pages of 400-year-old manuscripts with the reverence of someone who understands that some knowledge can’t be digitized. At 64, he has spent more years within monastery walls than most people spend in their entire careers

Karma’s hands still show the faint marks of keyboard impressions after five years away from Delhi’s glass towers. At 34, he moves with the unhurried confidence of someone who’s learned the difference between being busy and being purposeful.

Devi aunty’s weathered hands move like conductors interpreting a symphony only she can hear. At 67, she reads mountain skies with accuracy that puts meteorological departments to shame.

Devi Lal’s eyes hold the kind of clarity that comes from 82 years of breathing air so thin it strips away everything unnecessary. His weathered hands gesture toward peaks that have been his neighbors since birth, speaking of them like old friends who occasionally demand respect.

Laxmi aunty’s hands tell the story of 50 years spent nurturing leaves that would travel the world. At 73, she can still feel the exact moment a tea leaf is ready to be picked – “The plant whispers to you, but only if you’re listening.”